Tomorrow’s planes will fly on sustainable fuels!

You may soon be traveling in an airplane run on fuel made from used cooking oil! Safran is already working on sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), or biofuels, to reach the goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Below, we take a closer look at how Safran is meeting this two-pronged technical and ecological challenge.

- ELECTRIFICATION

- E-TAXIING

- INTERIORS

- At a glance

- Zoom

Tomorrow’s aviation fuels must be sustainable – that’s the goal set by Safran and the aviation industry in general to meet the target of net-zero carbon emissions by about 2050. It’s a hefty challenge, but solutions already exist. One of our approaches is to improve aircraft energy efficiency, in particular thanks to the gradual replacement of conventional jet fuel by alternative “sustainable” fuels.

Nicolas Jeuland

These sustainable fuels offer a key advantage, since they reduce CO2 emissions by about 80% over the entire lifecycle.

Biofuels, often made from biomass, would reduce CO2 emissions by 80% – quite an advantage! Another key benefit is that they’re drop-in, meaning they can be used right now without having to modify the aircraft, operating procedures or airport infrastructure.

Seven different aviation biofuel processes have already been certified, and six of them are producing fuels that can be used in a 50/50 blend with jet fuel. Safran favors biofuels made from vegetal waste, since their production doesn’t compete with food crops. In practical terms, SAFs could be made from food or agricultural waste.

In September 2021, Safran and TotalEnergies signed a strategic partnership agreement to jointly develop solutions to foster the emergence of a viable SAF industry.

Since then, both ground and flight tests of airplanes and helicopters using SAF have flourished. On October 14, 2021, a Boeing 737 MAX-8 powered by CFM LEAP-1B engines flew on nothing but SAF. In February 2022, Safran Helicopters Engines, working with TotalEnergies and Airbus Helicopters, conducted the first flight test of an NH90 helicopter in which one of the two engines used a biofuel. Even military aircraft are entering the decarbonization race. In July 2022, an Airbus A400M airlifter carried out a test flight with one of its TP400 turboprop engines using a fuel blend containing 29% SAF.

And the results?

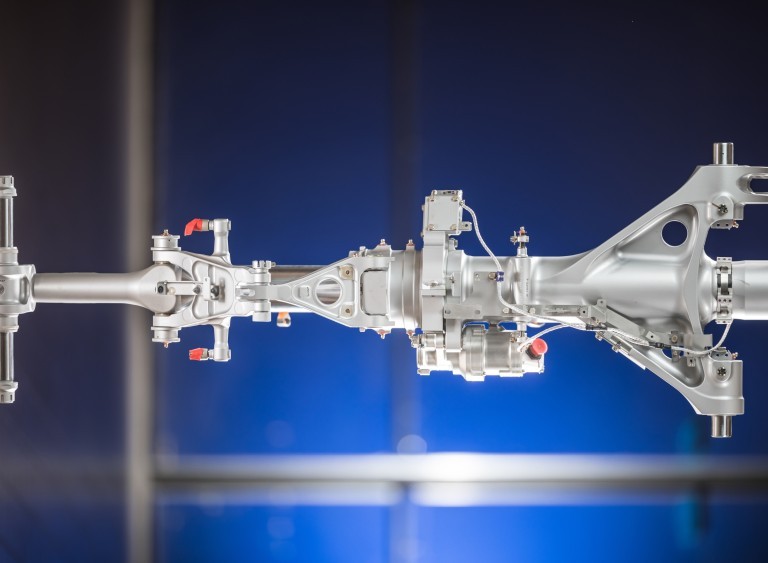

The European Commission launched the JETSCREEN research project in 2017 to better understand the impact of SAF on fuel systems. Safran Aerosystems was a major player in this project, since it makes fuel quantity measuring and distribution systems.

The follow-up VOLCAN project was launched in 2021 by Airbus in a consortium including ONERA (the French aerospace research agency), Dassault and Safran, with the participation Safran Aerosystems, Safran Aircraft Engines, Safran Helicopter Engines, Safran Filtration Systems and Safran Tech. VOLCAN aims to study the impact of sustainable fuels without aromatics or sulfur to get a better idea of how these fuels affect the aircraft (compatibility with engines and fuel system) and also how the fuel affects the engine’s emissions and contrails.

Despite what you sometimes hear, the aim of these emissions measurement programs is not to measure the reduction in CO2.

In fact, burning sustainable fuels releases virtually the same amount of CO2 as burning conventional fossil fuels. The advantage of sustainable fuels comes from the full lifecycle, since the CO2 released during operation had already been captured during the fuel production process.

The first flight test of a single-aisle commercial jet flying with 100% SAF took place on October 28, 2021 as part of the VOLCAN project.

Spotlight on hydrogen, the zero-emissions aviation fuel

Hydrogen is a primary research focus and may eventually replace jet fuel on some aircraft, whether in liquid or gaseous form, pure or synthetic. Safran is working on three possible scenarios:

- –

In cryogenic form, i.e. liquid hydrogen at -253 °C, to be used directly in the aircraft. This is an attractive solution because burning hydrogen only emits water, theoretically… but it also requires a number of major changes in fuel storage and distribution systems.

- –

Hydrogen could also be associated with CO2 captured from the atmosphere or industrial releases to fabricate a synthetic kerosene. The advantage of this type of “electrofuel”, also known as “Power-to-Liquid”, is that it’s compatible with current aircraft and distribution systems.

- –

Hydrogen used in a fuel cell is also a possibility, but this type of power source would be limited to smaller aircraft.